This page was originally written as part of speaker prep for the TBS – The Big Sick conference. It will be fine tuned it over time. We offer this to others who want to up their presentation game or who are in charge of running conferences. It shamelessly builds on a lot of other open source resources, linked at the bottom. Use what you can.

3 main points

- public speaking is like theatre. The story and the spoken word are the driving forces

- visuals in the form of slides will impede or outright kill your presentation if used without focus and intent

- rehearse your presentation. For your own sake and that of your audience

These 3 insights motivate 3 domains that you need to focus on

- The Story (p1)

- The Supportive Media (p2)

- The Delivery (p3)

Visit Ross Fisher’s site for more on this “p cubed” mental model.

THE CURSE OF POWERPOINT

When we feel the need to do this introduction to presentation theory, it is in large part due to the common misuse of slides. A few words about that.

The visuals of Powerpoint and Keynote have taken over as the main product of many presentations.

We have all suffered through talks where the speaker used slides like a manuscript, sometimes reading the content verbatim, or used impossible-to-read text, bullet points and detailed tables, graphs and front pages from articles.

Used this way, slides effectively work AGAINST your presentation. We often refer to it as being “killed by powerpoint”.

This was never the intention. It’s called a talk for a reason. Your talk is NOT your slides.

Give Tessa a follow for high yield tips on presentations

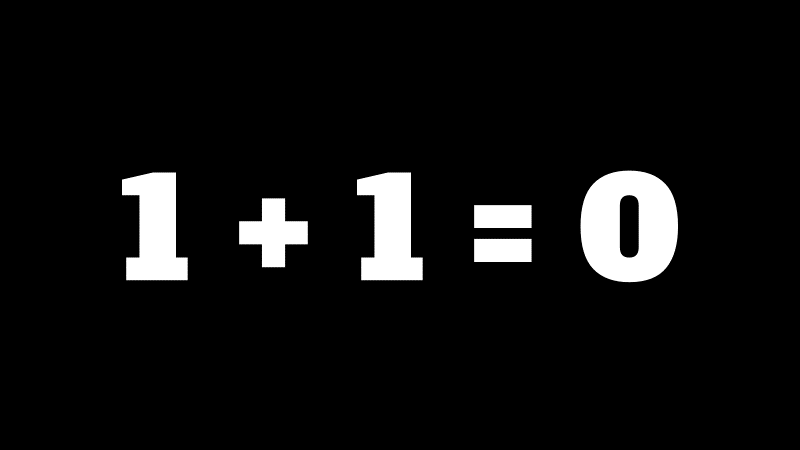

Psychology research teaches us that the human mind can process only one language stream at any time. We can read. Or listen. Not both.

And for some reason we’re wired to prioritise visuals first.

Put more than a few words on a slide and people will drown out your voice as they hear themselves read the text or try to understand a graph. You effectively lose their attention.

Therefore, you should let your spoken word and the power of your story carry the talk. Everything else is just supportive.

It may be helpful to imagine yourself doing your talk sitting around a camp fire. If you have your message, story and delivery in place, that talk will have no distractions and be so much more engaging. Work with the aim of being able to do the talk convincingly with you words and presence alone. Slides can be useful, but they are at most a prop in your performance. It’s your name on the ticket, not Microsoft.

Ich bin ein Berliner. Keine slides

I have a dream. No slides

WHAT’S YOUR MISSION?

It may feel megalomaniac to think of, but in the end you’re on stage to make a dent in the world, however big or small. You have to know why you’re giving the talk. You need to identify what change you seek, your mission so to speak. Somehow, in some way, you being there should change the world for the better. If you don’t know and can articulate why the audience should care, they won’t.

You will have heard about the concept ”elevator pitch”. The idea is to be able to express in 30 seconds (the time it takes on the elevator ride) why people should want to hear your talk. To do that you need a clear picture of why it matters. If you can’t do that, chances are your thinking isn’t sufficiently destilled. Before the What comes the Why, or as Ross Fisher would put it, you need look not for the What, but the So What?

START ANALOG

Now, if you take only one thing from this post let it be this: Do NOT start developing your thinking on the computer. If you end up using slides the crafting of them comes later as the mission and the arc of your talk have fully developed. Opening up your computer will distract you and stifle your creativity. The urge will be strong. But really, don’t. It makes a huge difference.

Go analog. Use paper and pen. Work with your ideas physically. Jot down ideas, push them around. Take a walk. Talk to a colleague. Sleep on it, let it marinate, leave and come back. This is a much better way to set free your creativity and develop the core message and storyline. See this post as inspiration to planning your talk.

WHO’S THE AUDIENCE?

Having identified your mission you need to consider how to achieve it.

Any talk is targeted at an audience and they will be the vehicle for your change, so thinking about them is key

Ask yourself

- who are they?

- what do you want them to change?

Making people change is not easy. You need to understand the starting position of your audience. Engage them there. Guide them to see the problem through their eyes. Make them care, you must.

CRAFT YOUR STORY

To do that, you need a story that grips and holds on. Classical rhetorical virtues going back to Aristotle are still in fashion. Concepts like story arcs, performance, and appeal to pathos, logos and ethos.

Again, public speaking is a form of theatre.

There is a common misconception that entertainment and professionalism are at odds. In reality, it is the other way around. If you want to effect change – and why else bother? – you need to be able to entertain. Entertainment is the art of engagement, not the enemy of science.

Now, there are many ways to skin a cat, and your presentation will be all the better for reflecting and channelling your personality. However, the successful talk often adheres to established ideas of start-middle-finish.

HOOK

Think about a strong start. You need a “hook” to reel in people and get them invested from the get go.

Something relatable, either a personal experience of your own, a case, or a dilemma that you imagine the audience will be able to see themselves in. Vulnerability and authenticity can be very important tools. There is no cheating in evoking emotions – quite the contrary, there needs to be something on the line.

Try to identify a conflict that needs to be resolved. It’s like pulling back the string of a bow. Your talk needs that tension to propel it forward. That secures buy-in and attentiveness to your arguments as you and the audience together move towards a resolution that will contain the change your want them to enact.

MIDDLE

The middle should investigate the details of the defining issue and its possible solutions. You would do well to consider a worthy opponent’s alternate solutions and address them.

Be cognizant of these different sub plots of your talk and what each of them achieves. Build a mental map of them and consider writing them out on paper as a physical storyboard which will help when you rehearse your delivery.

Surprises can work effectively as you develop the plot. Maybe things aren’t what they seemed to be? However, as listeners we find it easier to follow a talk where the overall structure of the presentation is not surprising. It can be useful to deploy a clear structure and signpost different parts to be covered, circling back and doing recaps as you move along. Good story telling often employs repetition. There is a reason 3 and 7 feature so prominently in fairy tales.

Your time slot is deliberately not more than about 20 minutes because we know it is almost impossible to keep people engaged longer than that. Even then, it is often a valuable addition to your talk to specifically activate the audience by, for instance, putting up a vote or asking them to discuss a dilemma for a moment with the person next to them.

FINISH

Overall, having presented the driving dilemma and investigated its details and possible solutions you’ll be building to a central point in your talk where you resolve the conflict and the core message lands. Make sure this can not be missed. It should be as clear as day and contain one or at most a few actionable take homes. You’ll hopefully have convinced the audience of the necessity of the change you suggest and made them own that idea.

PROPS DONE PROPERLY

When your talk is fully developed, you should be able to give it with little or no added elements. This is when you start looking at things that could help you enforce the performance. Many of the best talks employ no extra help, but they can help if you are deliberate about it.

Think of it like ‘props’ in your theatre play.

Physical objects can work, sometimes surprisingly well. Music and sounds are also very evocative elements.

Oftentimes, mostly out of habit, we end up using visuals in the form of slides. If this is your path, a few words on how to improve the use of them.

How to better use slides

Illustrate, don’t annotate

Remember, the audience needs to hear your arguments, not read them. Your slides should support the story, not contain it. They are neither your script nor your handout.

A recurring problem is using too much information. We often know it. Who in all earnest has not apologised for a slide that was a bit “busy”?

Text is especially problematic, as that invariably has the audience reading to themselves, but cut-outs of complicated tables or graphs also takes time for the audience to decode during which they won’t listen. It is NEVER a good idea to copy-past from other documents (articles, web pages etc) – the written delivery in other media is fundamentally at odds with your mission while presenting.

Remember, we don’t need every p-value, subgroup analysis and forrest plot. You are on stage precisely because we know you’re an expert in your field. We are interested in your take on the data, your summation of it, the meaning of it. By all means argue your case, but don’t give us every little detail.

Start with blank slides. Depending on the location and your plan, a black background can be a good choice as a big white screen lights up the room even when nothing’s on. Avoid templates from work – they come off drab and add nothing to your talk. We know where you work.

Cut down. Don’t compete with your slides. There doesn’t have to be something on the screen all the time.

Consider intermittent empty black slides to pull the focus and connection back to you.

Imagery

Pictures, they say, convey more than a 1000 words. Use them. They are great at setting a mood and can illustrate in a second what’s at stake. Pictures with a few words in a big font size work potentially even better. You’ll find examples on this page.

Use pictures of high resolution unless you have a specific creative idea going low res. In general fill the frame for maximum immersion. Crop and center as needed to highlight what’s most important.

You can find good free images from unsplash, flickr,com, pixabay.com, pexels.com, and this “openverse” search engine. You will also likely have access to paid stock image libraries through your workplace that will be OK to use for education.

A word of caution: If you use google image search and filter for open access images you need to check with the actual source page as google often gets this wrong.

Artificial intelligence is now on offer too with a multitude of text-to-image models to generate pictures in any style. At the time of writing big ones are DALL-E2 (from OpenAI who also does chat-GPT), Midjourney, and Stable diffusion (open access model) or for instance the Freepik search engine that allows you to search across AI and non-AI.

Videos can be an excellent addition to your talk, but make sure you download and embed them as you cannot expect online to work. Be mindful that videos from youtube and vimeo in general have copyrights and are not necessarily OK to be used in your presentation, especially if your talk is also going online.

Sometimes using images, audio and video of your own making will be more personal than “stock” footage that you try to make fit your message.

What about the data?

Some will argue it can’t all be pretty pictures and that this approach dumbs it down, that we need to discuss the data. And yes, of course we need to discuss the data. The above just advocates, based on good science, that you engineer your slides according to basic human constraints. We have all trained extensively in CRM principles and this is just applying that same human factors appreciation to the speaker-audience dynamic.

Of course you should do a deep dive on those amazing details in the data when that propels the story. Share your enthusiasm, geek out, but don’t have us choose between following your talk and reading the slides.

Make sure you design your media to support your points, data slides included. They should be understood in seconds. Work on their signal to noise ratio. It’s not Where’s Wally (Waldo for those in US/CAN). If you include important text, allow people time to read, and pause talking while they do.

Fundamentally, there is only so much you can convey in 20 minutes. The reason you are there is you have spent thousands of hours condensing the data for us. That data can’t all go on the slides and is better left referenced in a handout, the form of which these days might be along your talk online, for instance in a blog post with further details that you can share at the end of your presentation, eg with a QR code. That will allow people to dig deeper at their leisure.

REHEARSAL

Rehearse your talk.

Every talk will be markedly better for it. Don’t underestimate what this will do for your audience, but equally important, for how you feel on stage.

Again, public speaking is like theatre. A typical conference has a scene with backdrop, lights, AV, a set programme with intermissions and a discerning audience in the room, plus online.

Rehearse.

GET UP

It won’t help much to sit down with your slide deck and mumble to yourself “I say this, and then bring this slide up, have to remember this point” etc. Only when you stand up and actually say out every word and advance every slide do you experience where your story and delivery works and where it can be optimised.

The more times you do so, the better. Scott Weingart, educational master of EMCrit fame recommends 7 levels of rehearsal. While that is beyond most of us, it is true that every take will find details to correct. A superfluous slide. A timing that needs to change. A flawed logic. Kill your darlings.

Use the mindmap of stages of your talk, post it notes can help, so you know how far you’ve come and where you are headed.

Know your slides and transitions by heart. Work to come in at significantly under your allotted time. No one ever complained about a talk being too short. That way you have room to breathe and enjoy yourself. Which you will if you have the confidence from rehearsing well.

PERFORM

Your delivery of the talk is not just remembering it all and having nice slides. You need to act it. Again, public speaking is theatre.

Rhetorical studies tell us body language and voice is more important than any of the content you share in persuading an audience.

Rehearsal will help tremendously with this. It will also take your nerves off.

Think about what energy you bring. Your body language. The tone of your voice. Your pitch, the volume. The use of your arms. Your breathing. Where do you look? Do you have vocal tics? Do you smile? Do you pause?

Don’t overload the audience with a non-stop monotone stream of info. Experiment with pauses and shifts in tempo and volume. Leave points some time to land. People will relax and listen more if they have some time to digest and reflect. Try to be authentic and connect with the audience. Relax and enjoy being on stage. Nobody expects perfect and we quite enjoy someone human, flaws and all. Remember, the audience wants you to succeed.

GET FEEDBACK

As you rehearse, it is a really valuable eye opener to set your mobile phone to record you. It will probably make you cringe, but you will learn a lot and be able to address your performance imperfections in a targeted way.

When you are ready, consider letting family, friends or colleagues give you feedback. Choose people you trust. They will notice things you never could and give you invaluable feedback.

FINALLY

It might sound like there’s one perfect and unattainable way to do things. There isn’t.

In some ways it’s the other way round. We want to move away from the-one-way-it-has-always-been-done which objectively has not worked and empower you to try your own way. We put a high price on variation and geekiness. Use your imagination and above all, have som fun with it.

I remain open for sparring about anything related to your talk. Reach out to me on twitter or email.

If you want more on presentation and learning theory I suggest these resources as a start.

I’ve shamelessly used a lot from them above.

Ross Fisher

Ross is a paediatric surgeon in Sheffield on his day job, but except to the families he looks after he is probably more widely known for his great passion for helping the field of medicine improve the yield of presentations, one keynote and one workshop at a time. This has taken him round the world including to our shores and he is a major inspiration. His website is full of excellent posts. I can specifically recommend you start with How to do a presentation and this case study of him preparing for a talk of his own.

Ross recently delivered two webinars for our local Scandinavian anaesthesia society which have a homy, intimate feel to them. If you get a chance to go to a workshop with him, do so.

Garr Reynolds

Presentation sensei and author of Presentation Zen, a seminal text that set off Ross on his path.

He also has a great website with tons of good stuff. Worth a follow on twitter.

Better Presentations – Kate Jurd

Kate Jurd is an educationalist from the University of Queensland.

She is behind this very well presented open access masterclass on improving presentations that goes in much more details with everything than I could. It covers the science quite well too. Great one stop resource.

Powerpoint and Meth – Scott Weingart

This post nicely illustrates the work behind the success of the man and his EMCrit site. That stuff doesn’t happen at random. As of recent subscribers only, but the site is more than worth the price of entry.

Fixing a slideset – case study

Associate Prof Franz Babl handed in his usual academic slideset for a paediatric conference and courageously allowed presentation geek Gracie Leo to work with him on a transforming it into a more modern version.

Very illustrative on how to successfully convert dense data slides.

Find it on Don’t forget the bubbles. More on presentations from Gracie here.

Getting feedback on your performance

Reuben Strayer, NYC EM physician and frequent speaker, had the guts to get professional feedback from an acting coach on a very well rehearsed talk at SMACCDub. Lots of insights from another profession.

Tim Montrief

While revisiting this topic I happened on this tweetorial with 10 tips for better presentations which I found excellent and to the point. If you’re the twitter kind you can find more convo on the topic of presentations at #presentationskills and #htdap (how to do a presentation).

Richard Smith

Former editor of the BMJ and outspoken proponent of reforming the publishing industry and scientific merit system, Richard also made this hilarious take on how to make sure your presentation is as bad as your peers.

PIXAR in a box

If you are curious about how some of the brightest minds in the creative industry craft a compelling story and deliver it I recommend this series from PIXAR, now hosted on KhanAcademy. It is quite clever and engaging (you’d hope so, case in point). Although the scope and tools extend well beyond doing a talk there are some principles of story telling here that are very applicable.

Scandinavian paediatric anaesthetist / intensivist.

PHARM, ED, OR, ICU.

Digital MedEd

Co-founder scanFOAM.org

Co-organiser CphCC & TBS-Zermatt (aka The Big Sick)

Medical lead REPEL (resilience in pediatric emergency life support)

Web dev SSAI.info