As newly graduated medical students leave universities around the world and start their professional lives as junior doctors, so starts the media coverage about the #JulyEffect (1).

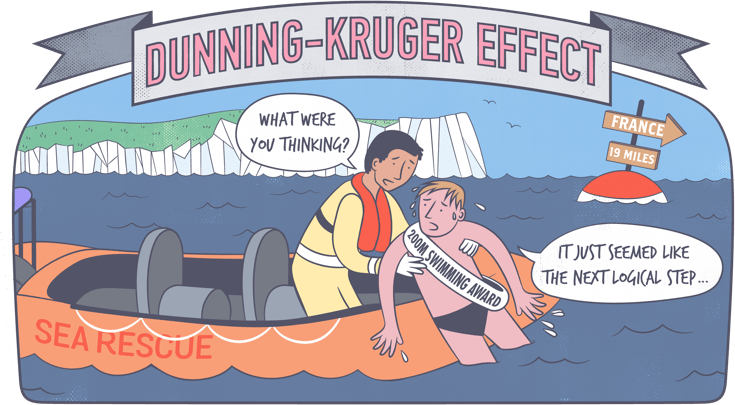

The Dunning-Kruger effect is cited frequently in medical education and is sure to come up in connection to the conversation about the #JulyEffect. And with good reason (2). As novices enter the clinical setting being aware of this effect is indeed important because junior doctors are at increased risk of being unaware of their own limitations and thus pose a risk to themselves, to you and to patient safety.

The #JulyEffect doesn’t, however, solely pertain to the recently-graduated-from-med-school population (3). First year residents become second year residents with increased responsibilities, graduating residents become attendings/consultants and so on. So really, practitioners breaking into new roles at all levels contribute to the #JulyEffect. And then, after finally achieving proficiency and expert status, that too comes with its share of struggles. How do you stay on the “path of sustainability and expert performance”?

So for once in July, instead of lamenting the challenges of saving novices from themselves as they rush up Mount Stupid, let’s take a look at the role and challenges of an expert provider and some of the positive parts the novice practitioner can play.

What makes an expert, and what’s expertise?

An expert is “someone who is very skillful and well-informed in some special field” (4) and expertise refers to “the characteristics, skills and knowledge that distinguish experts from novices* and less experienced people” (5).(* the term novice refers to a range of non-experts)

This table lists categories of proficiency (adapted from Hoffman 1998) (6).

Research on expertise is often focused on what positive characteristics experts possess and how they perform (better) in comparison to novices. However, knowing how experts fail and when you as an expert need to be aware of your own limitations is just as important for safe patient care and effective role modeling for your novices.

7 ways you may fail as an expert (and how novices can help)

This here is a list of 7 ways you, the expert clinician, might be at risk of falling short and how your novice may just be part of what the doctor ordered to save you.

1) Your expertise is domain-limited

And, unfortunately you don’t excel in remembering what you once learned within another domain.

How your novice learner can help

Sometimes, just sometimes we present in your department well aware of the newest knowledge within a topic. We may just have read or learned something that has changed since you learned it. Don’t dismiss us. Ask us where we found that knowledge and help us apply it in practice.

2) Sometimes you too can be overly confident

You over-estimate how much you think you know and sometimes novices are actually more accurate. How does this differ from Dunning-Kruger? You are perfectly aware that you don’t know everything, and that you need to ask for help when you move outside your domain. However you have a tendency to overestimate your capabilities within your area of expertise.

How your novice learner can help

When you meet our over-confident and unaware approach and tell us to be overly cautious and conservative remember that you are also prone to risk taking. And the threats that comes from risk taking they sometimes become fatal errors. So look out.

3) Sometimes you “gloss over things”

No doubt you know what you know. And you have in-depth knowledge within your area of expertise in a way we can only dream of. But sometimes you miss the details.

How your novice learner can help

When you tell us to be overly cautious and conservative, respect when we are just that and sometimes insist that due to our overly thorough examination of a patient we believe that something is wrong and not just business as usual. We may be right. You may have missed something.

4) You rely on contextual cues

You rely on things adding up! Age, sex, previous history, co-morbidities etc for making a diagnosis. This is not always related to disease. But your expertise and your experience with patients help your decision making and you are about 50% more accurate than your novice.

How your novice learner can help

Or how you can help us help you! Teach us the art of asking the right questions so we become better at clinical decision making. We are trying rather hard on our own and would appreciate your help.

5) Sometimes you are inflexible

I know you aim for adaptive and flexible expertise. But that is a description of exceptional expertise. Your regular expert can come off as inflexible because sometimes things change. And you are not always a fan of things changing when you’re comfortable with what you know and are good at.

How your novice learner can help

We are pretty good at asking “why?” or reminding you that we just learned differently from one of your colleagues. Realize that by asking all these questions and by challenging you we actually help you stay or become and adaptive and flexible expert, and you really want that.

6) Sometimes you are inaccurate in your prediction of novice performance

Yep, I said it, but I don’t mean it in the way you may fear. Sometimes you forget that we, your novice learners, need time. You can’t really predict how much time we need to spend on performing tasks and talking to patients, simply because you’re so God damn good at it.

And by the way. When it comes to making decisions under uncertainty: We suck equally much.

How your novice learner can help

Engage your junior faculty in skill training and feedback. A second year can teach a first year and your new attendings and fellows can train and teach your senior residents. Novice learners learn novice tasks and skills way better from peers and the feedback given from peers are way better received and incorporated than feedback coming from experts. (You may, however, ask your learner all the questions you want and help them reflect on everything learned).

7) Sometimes you are rather biased

That is, you tend to fall pray to selective attention and confirmation bias or you’re prone to the illusion of frequency. If you’re a cardiologist you’ll think something’s wrong with the patient’s heart, a neurologist the brain and so on. Our friends at St.Emlyn’s have published an excellent blog post on the topic written by Chris Gray @cgraydoc .

How your novice learner can help

We are ridiculously well-trained in making differential diagnoses and can still remember all of them. Let’s look for the zebras once in a while, when we suspect it may be those hooves we are hearing. We both learn from this and the occasional patients for whom we change management to the better will thank us.

Really? I’m that bad?

In case this blog post made you feel awful in a way you haven’t felt since the day you fell from the top of Mount Stupid as a junior, remember that experts excel in these seven ways as well:

- By generating the best solutions and you do this much faster than your juniors

- You see patterns and features and connections juniors can’t even think of

- You analyze problems by making use of many different domain-specific skills. Your junior may not even know what domain-specific means.

- You are not as prone to the Dunning-Kruger effect at novices – you are better at self-monitoring and self-assessment

- You are way better at choosing the appropriate strategy in any given situation. The end!

- You are more opportunistic than novices, and better at getting away with it.

- Your cognitive bandwith is just so much greater….and we envy you.

At the end of the day, we wouldn’t survive 5 minutes in the ED without you looking over our shoulder so thank you for all your support and feedback!

XOXO your Novice (Sandra)

[Ed: expertly reviewed by an old curmudgeon /Mads]

Disclaimer:

This post is build on chapter 2 in the book below which details the above 7 features of failing experts (7). The suggestions on how novices can help is solely personal non-expert opinion.

The book can be bought from Amazon here (non affiliated)

References:

- http://edition.cnn.com/2016/07/04/health/dont-go-to-the-hospital-in-july/

- Kruger, J. and D. Dunning (1999). “Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments.” J Pers Soc Psychol 77(6): 1121-1134.

- Petrilli, C. M., J. Del Valle and V. Chopra (2016). “Why July Matters.” Acad Med 91(7): 910-912

- http://www.yourdictionary.com/expert#websters

- Ericsson, K.A. (2006) An Introduction To Cambridge Handbook Of Expertise And Expert Performance: Its’ Development, Organization, And Content. In Ericsson, K. A., Charness, N., Feltovich, P., & Hoffman, R. (Eds.). Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (pp. 3-20). New York: Cambridge University Press

- Hoffman, R. R., Crandall, B., & Shadbolt, N. (1998). A case study in cognitive task analysis methodology: The critical decision method for the elicitation of expert knowledge. Human Factors, 40, 254-276.

- Chi, M.T.H. (2006) Two Approaches To The Study Of Experts’ characteritics. In Ericsson, K. A., Charness, N., Feltovich, P., & Hoffman, R. (Eds.). Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (pp. 21-30). New York: Cambridge University Press

Star skater, simulationista by day, anaesthesia by night and #meded choreographer. Coming to a SIM room near you. With a shark.